The Disease of Disenfranchisement

The sun shone brightly on primary day 2020 in Chicago as the levers of democracy were illuminated throughout Illinois. It was March 17th, four days before Illinois Governor J.B. Pritzker announced he was placing the state under a stay-at-home order. Over 500,000 people flocked to their polling locations in community centers, churches and gyms across the city despite an increasing wariness over the global pandemic.

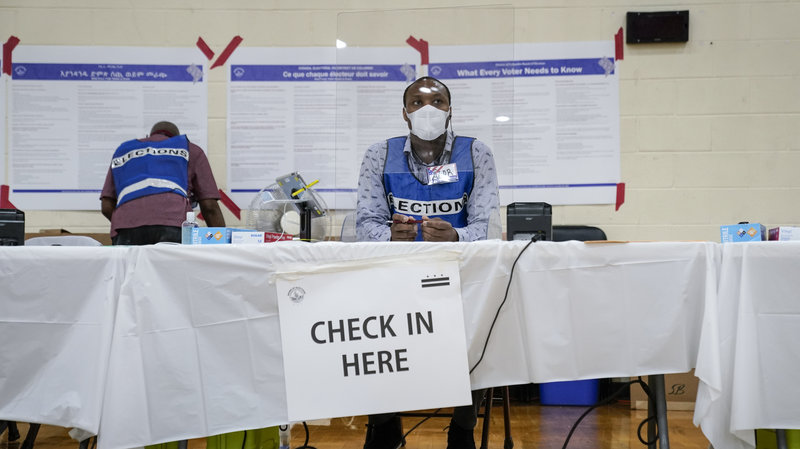

It was just two weeks later on April 1, that Chicago’s first city employee died of Covid-19. His name was Revall Burke and he had worked as an election judge on West 78th Street during the primary.

Among the effects of the novel coronavirus crisis, is the pressure it places on the upcoming election on November 3rd 2020, and its preceding primary elections. Now many are asking, "how do we maintain citizens’ physical health and a healthy democracy?"

“We really dodged a bullet.”

The first major collision of the coronavirus pandemic and the 2020 election was distilled as the Wisconsin primary. As panic over the pandemic intensified in the weeks before the scheduled election date of April 7, Democratic Gov. Tony Evers began attempts to adjust the election. He first asked his state’s legislature to send mail-in ballots to every registered voter but a majority of the lawmakers denied the proposal. Then, on the day before the election, he ordered a two month postponement but it was overturned by the Wisconsin Supreme Court. A bungled and confusing election took place the next day that exacerbated the health crisis after at least 40 people contracted the virus in connection with visiting a polling site.

Poppy Niosi was disappointed in the trepidation that came with exercising her right to vote that day in her native city of Madison, especially seeing that not everyone at the polling place, even the people working it, had masks on. “I was going to make it happen no matter what. But the thought of having to risk my life to vote was upsetting,” she said.

“There was no real push to get people to vote absentee, there wasn't a lot of information, I didn’t see anything until the day it was due,” Niosi said.

In the wake of the example set by Wisconsin, and subsequent primaries, the upcoming general election, which will decide the presidency and potentially the course of the country, many states are now using these next months to rework their voting processes. But adding to the confusion of the moment is the fact that there is not a national standard for election processes in each of the 50 states meaning individual state government’s are in charge of their own election system.

“Wisconsin was an example of what we don't want in Minnesota or anywhere else in the country for that matter, said Minnesota Secretary of State, Steve Simon, whose office is charged with carrying out the election. “A situation where people were put in a position of choosing between their health and their right to vote.”

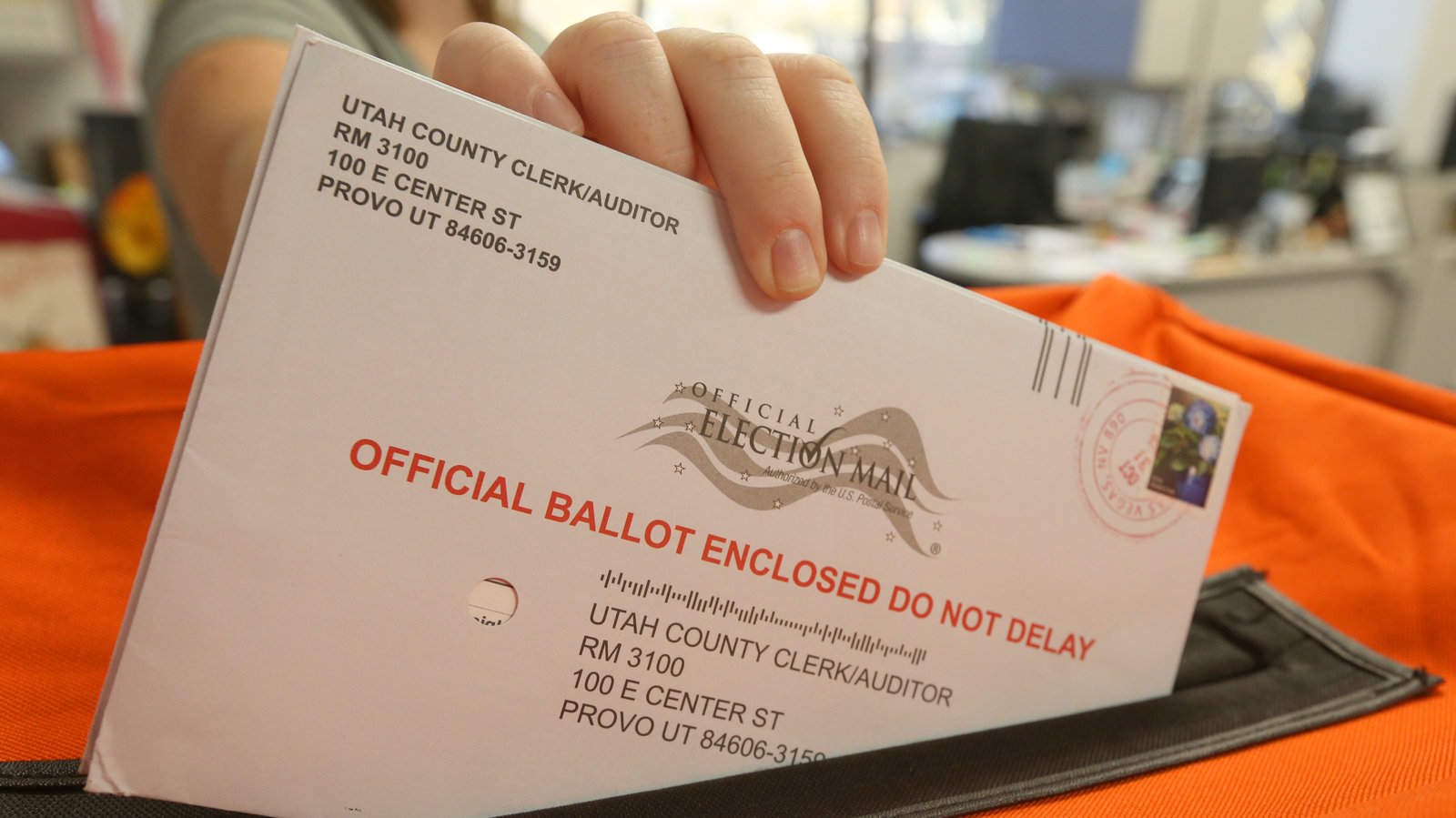

The leading approach for fortifying social distancing measures is through mail-in voting. Voters receive a ballot in the mail, either by request or automatically when they register to vote depending on the state, and send it back to be counted. Similarly, absentee voting refers to ballots being sent through the mail to people who cannot be present at their polling site on election day. Twenty-nine states already have no-excuse absentee-balloting where the voter does not have to explain why they cannot vote in person. 16 states have excuse-only absentee-voting and five states have a nearly complete vote-by-mail election system where voting occurs primarily through the mail. Though technically different, absentee and vote-by-mail can be used interchangeably in this scenario.

Following the March 17th Illinois primary in late May the Illinois Legislature passed a temporary election bill, “We knew we could be facing a much worse situation in November.” said Illinois Board of Elections (IBE) representative Matt Dietrich.

In Illinois, anyone who voted in the last three elections, including mayoral races, will automatically be sent an application for an absentee ballot. That's about 5 million voters according to Dietrich. More deviations from normal election procedures include that applications can be sent back immediately, while usually they would have to wait until August to request an absentee ballot. Ballots do not need to be postmarked to be counted, also a dissention from precedent.

Dietrich says the measures the new law accounts for are vital after what he saw happened after the primary election when COVID-19 rates precipitously increased.

“We really dodged a bullet. The day after it just skyrocketed,”

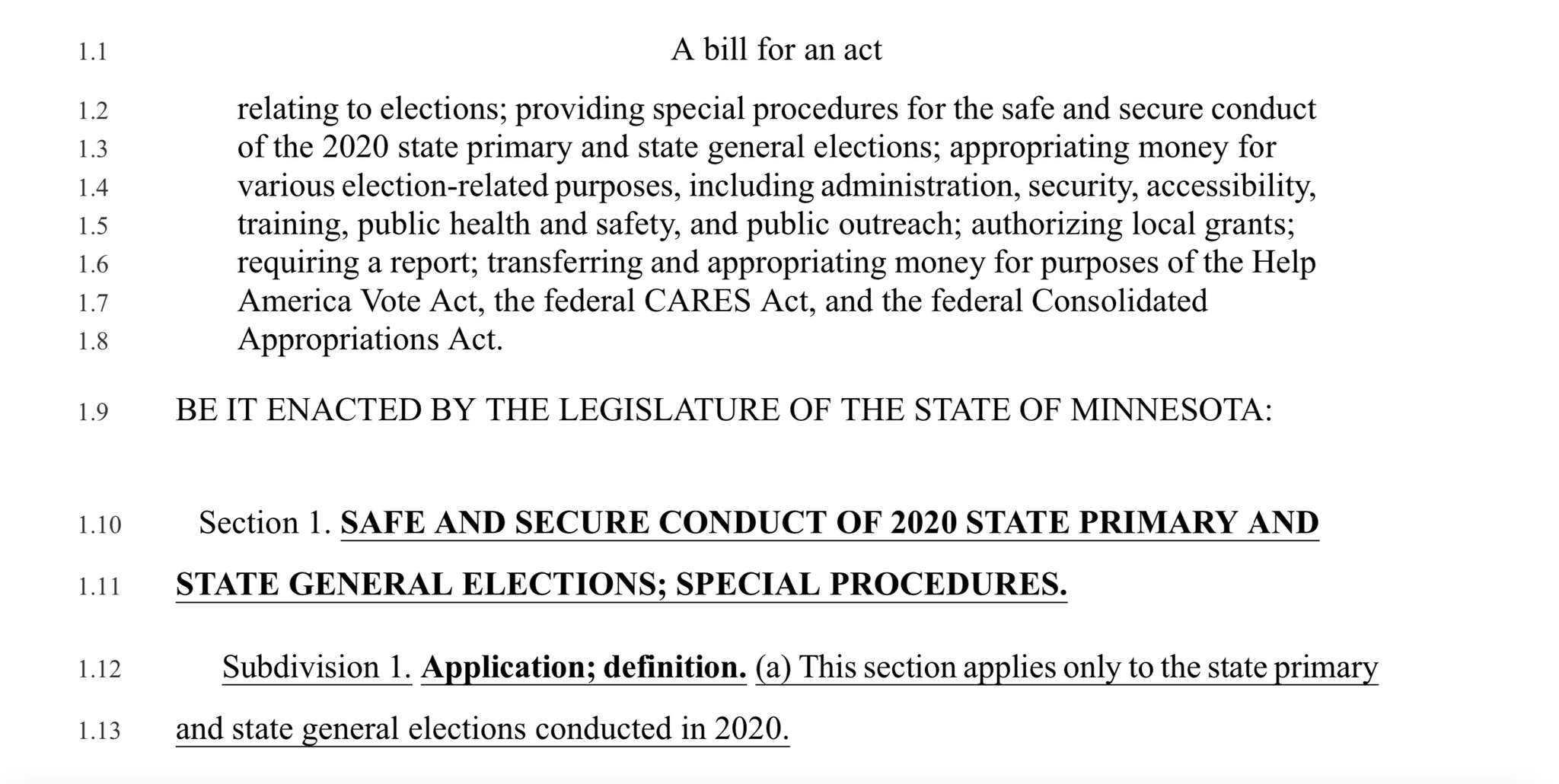

In Minnesota, Secretary Simon was instrumental in brokering an election bill in the Minnesota Legislature that was signed into law in May by Democratic Governor Tim Walz. It includes provisions like eight additional days for processing absentee ballots.

However the final draft of the bill didn’t include everything Simon had pushed for. Republicans in the Minnesota legislature pushed back against universal vote-by-mail, a move that would have completely disbanded in-person voting. Lawmakers attempts to stymie this frustrated Simon who points to a law Minnesota has had since 1987 that allows certain jurisdictions, if they choose, to send all their voters ballot automatically for every election. Simon says 130,000 people live in those communities: “This is not a scary or radical idea.”

But what Simon is most perturbed by in not having universal vote-by-mail is that now voters have to request the ballot by mail, instead of automatically being sent one.

“They have to affirmatively do something. The onus is on them. The burden is on them,” he said.

But others who are also advocating for enfranchisement amid the pandemic are wary of a complete shutdown of all in-person polling sites, fearing it could harm marginalized populations.

“We're definitely not where we should be when it comes to modernizing elections”

Timna Axel, director of communications for The Chicago Lawyers Committee for Civil Rights (CLCCR), a non-partisan organization that advocates for civil liberties, says it's vital to make sure that there's safe access for everyone, not just people who are privileged enough to be able to cast a mail in ballot.

“It’s not going to work to shut down the polling place in order to prevent people from getting sick, if that also completely prevents them from actually casting a ballot,” Axel said.

People of color disproportionately rely on in-person voting as compared to white people, a concern for Axel. “Folks who already faced more limited options because they're in disinvested communities and may have a more limited time window in order to go vote or may have limited transportation options to get to the polls would be a lot more impacted by things like that happening again in November,” she said.

The CLCCR is part of a consortium of advocacy organizations in Illinois called the Just Democracy Illinois Coalition, another partner in the coalition is Chicago Votes, a voting rights advocacy group based in the city.

Jen Dean, Deputy Director of Chicago Votes, says politicians need to have a racial equity lens in how they approach the task they’re faced with, something she says was already lacking, “We're definitely not where we should be when it comes to modernizing elections,” Dean said.

Dean is concerned about a multitude of factors that could impede someone’s ability to vote from home, like people who are experiencing homelessness or who have a criminal conviction and might not be able to have their name on a lease.

“How is that person in a previous condition going to get their ballot if they're not registered, and they don't have an address?” Dean said.

Axel echoes this concern. “Other groups see some serious issues there where you're creating two different classes of voters, folks who will receive a ballot and folks who won't.”

“The Words don’t do the Work”

The logistics involved with rearranging the election processes will be no small undertaking.

In Wisconsin, once the threat of the virus was clearly understood, thousands began applying for absentee ballots but the state didn’t have the time or resources to accommodate the surge. Niosi’s husband requested a mail-in ballot within the proper time frame but it never showed up and he had to decide whether or not to brace the polling site. He ended up going and in an ironic twist the absentee ballot he’d requested showed up the day after the election.

“We just tore it up,” Niosi said.

Illinois already allowed applying for an absentee ballot a few days before an election. But ostensible access to a mailed ballot isn’t a definitive bulwark against the disorganization that could erupt from a surge in requested ballots. This scenario played out again during Georgia’s June 9 primary when many reported not receiving their ballot in the mail and had to front hours long lines in the summer heat.

“They didn't have a long runway,” Simon said of Wisconsin. “We and other states, by contrast, have a few months now to act. So we need to take advantage of that. Handling what will be a tidal wave of requests of people who want their ballot mailed to them."

In response to this possible hazard, the Minnesota legislation increased the amount of time allowed to count the ballots sent in. Whereas previously, mailed-in ballots could only start being opened and tallied seven days out from the election, this can now happen at T-minus 14 days from election day.

Simon says Minnesota will also attempt to consolidate their polling sites around the state without starting a malign chain reaction. He points to Wisconsin where election judges didn’t want to show up, fearing for their safety, which led to hyper consolidation of polling places, therefore longer lines and a tougher experience that shut people out of voting.

“We see disenfranchisement every election. But of course, the pandemic is a special concern. Nobody should have risked their life in order to exercise their fundamental right to vote, but we've already seen that even in Chicago in the last election, which was already during the pandemic,” Axel said.

Jay Young, the executive director of Common Cause Illinois, a national organization that works to ensure voting rights are upheld, testified to the Illinois Board of Elections to push for the new legislation. He says the law is a good first step, though he wishes the board had made community input a written mandate.

“We’re in this situation where we have to figure out how to do this stuff at a distance. All of these strategies for meeting people where they are at have changed,” Young said.

Under the Illinois law, the secretary of state must send literature encouraging people to vote by mail, telling them about the right to vote by mail and containing language about COVID19.

But Young is wary that these outreach efforts will broadly work and is skeptical that they can break through the current types of disenfranchisement as well as those that are traditionally seen.

“The words don't do the work,” Young said.

From the perspective of government agencies like the IBE, some of the biggest challenges will come in the form of technological impediments. “There was some talk about whether it was even possible to meet that goal given the amount of programming that has to be done,” Dietrich said.

The confluence of the pandemic and the election highlights the intersection of health disparities and voting disparities faced by marginalized communities. COVID-19 has killed Black people at a higher rate than white people. Black people make up the disproportionate share of positive cases in both Illinois and in Minnesota.

“All of these various levers are pressing down and sadly all producing the same result that just in these communities that always seem to get left behind,” Young said. “I am hopeful that we won't see clear racial disparities in voter turnout But I expect to see them.”

Even after the dissolution of codified slavery, impeding access to Black people’s ability to vote has been a way to entrench systems of power and maintain a de facto the status quo of white supremacy in the United States.

In the early 1900s Southern states wrote into their constitutions restrictions that prevented Black people from voting, such as poll taxes, literacy tests and grandfather clauses. Until the 1940’s when the Supreme Court struck the practice down, Texas held all-white primaries. The Voting Rights Act has been law since 1965, but efforts to suppress the vote, like voter ID regulations, disproportionately curtail Black people from accessing their right to the ballot. A federal court found that North Carolina attempted to explicitly require forms of ID that black voters were least likely to have and in Georgia during the 2018 poll closures disproportionately affected the black population. In the same state two years later it was polling places in areas with predominantly black populations that bore the brunt of polling place stagnation earlier this month during Georgia's 2020 primary.

Milwaukee County, where the bulk of the polling sites during Wisconsin’s primary were closed, is majority black. Advocates are also worried that the risk associated with in-person voting will continue to harm people of color’s accessibility to the ballot through November.

Young says that the way the health crisis is playing out is consistent with the historic dearth of investment for certain communities and electoral inconsistencies. He doesn’t think the Illinois bill puts enough consideration into the structural disparities that might affect certain communities' ability to access the temporary reforms. By October 15th, the Illinois Secretary of State’s office will be required to send two reminders to all voters who've mailed applications, a letter strongly encouraging them to vote by mail. But Young isn’t sure that efforts like this will be enough.

“It’s tough to be poor, it's tough to be black it’s tough to be brown at a time when your access to healthcare is a challenge when you don’t have the luxury of working from your dining room table,” Young said. “The context in which we are putting families into and forcing them to make yet another important decision. People are trying to meet their basic needs not looking at an envelope sitting on their table.”

Though Dietrich says the Illinois Board of Elections echoes that thought, there are currently no language options besides English on the IBE’s online voter registration portal.

This alarms Axel who points out that it’s scary for people right now to go to the DMV and she worries that people who don’t speak English therefore won’t have a way to register to vote.

“That's a sign of a really weak and fragile democracy.”

The breakdown for who tried to hamper Simon’s efforts to adjust the upcoming election process was nearly split along party lines, with Republicans claiming that mail voting will lead to higher rates of voter fraud, echoing a, widely discredited and frequent talking point of President Trump’s, who himself has voted absentee.

Simon says their claims are erroneous, “That has no basis in reality,” he said. “I have to assume that some folks will take their cues from the president and basically declare war on the idea.”

Axel says Illinois has been lucky to have bipartisan consensus around election reform.

“When you have as many citizens as possible to have a voice in the governing of the country, then you're going to have more balanced power shared among these parties. The more you restrict that, the more of a monopoly you give to certain party members. That’s a sign of a weak and fragile democracy," Axel said.

Young says that in Illinois both sides of the aisle have entrenched their power.

“We have a system that is designed to produce outcomes that keep people in power,” Young said. “In some communities the racial impact of that becomes clearer. In Illinois, I am way more focused on our decision to hold [the people in] power’s effort to hold on to power."

The price tag attached to all the new considerations, like more people on payroll for longer and the necessary protective equipment for those working elections, is not small. The $2 trillion Coronavirus Aid, Relief and Economic Security Act (CARES), passed in March, allocated $400 million for election assistance. However, the Brennan Center for Justice estimates it will take $2 billion in total for states to adequately prepare for such significant changes.

Both Minnesota and Illinois state budgets will match 20% of what they receive from the federal government. Simon says the bulk of the added expenses to states and local election authorities will come from the waves of requests from people who want their ballot mailed to them-- which will incur costs for paper, envelopes, postage and paying for added processing labor.

“There is not enough money to buy everyone everything they need is enough money to help counties and cities offset their costs to match or help alleviate some of the financial burden,” Simon said.

Axel is nervous that even with the extra funds, there will still be a serious question of whether it will be enough to transition the system to effective and safe voting by mail.

“There is a lot of uncertainty whether the funding and the logistics could really happen in place and being placed in time for November. We all have to work with what's actually realistic in the next couple of months,” Axel observed.

Simon is especially nervous about poll workers not showing up for the job out of fear for their health. This happened in both Wisconsin, Illinois and, most recently, Georgia’s primaries. He doesn’t blame them for not wanting to potentially expose themselves to the virus, but the inadequate staffing is a major concern for November, as it was in Chicago back in March.

“We got calls from across the city,” Axel said. “Some places have just shut down at the last minute. They needed to reroute people to alternative locations, and that ended up creating enormous and crowded lines that were unsafe.”

In Milwaukee County only 5 of 180 polling places operated. The county is also home to the largest population of Black people in the state. The exorbitant consolidation and congestion was dangerous in a time when social distancing is one of the best defenses against the virus.

Still, with a goal of decreased in-person voter turnout in mind, the considerations for how to safely manage polling places weighs heavy on those who are working towards a true election.

According to Simon, there are at least 43 polling places around Minnesota that are nursing homes. “That's just insanity right now. That's inviting illness and possibly death,” he said.

Both Minnesota and Illinois will allocate federal and state funding towards personal protective equipment for poll workers and Minnesota will increase their pay to $20 an hour. Both states also lowered the minimum age requirement for election judges so that younger, less vulnerable populations could work the polls. According to Chicago Board of Elections (CBE) representative, Jim Allen, about 2,400 poll workers, representing one fifth of the total number of poll workers, in Chicago did not show up on election day. The CBE didn’t have data on which precincts were hit the hardest. Burke worked at a polling site in Chicago’s 17th Ward on the Southwest side of the city which was, at the time, the area with the most confirmed cases of the virus.

Illinois will also make November 3 a state holiday, meaning schools that would usually have students in them will be empty and able to be converted into a polling site in an effort to mitigate for high volumes of people even when nursing homes are not viable.

“It matters how well we can get those people to the polls”

The contest between President Donald Trump and presumptuous Democratic nominee Joe Biden is one of the most consequential elections in United States history. Down ballot races will also hold gravity.

It’s an election that could be won, or lost, on the margins. In Wisconsin, a court-ordered extension of when ballots could be sent back and counted resulted in an additional 79,000 ballots being tallied. President Trump won the state by just 23,000 votes in 2016. Every vote in November will hold weight.

Simon worries about an election day that will decide the fate of the country in an even more prominent way than any primary, that sees people excited to vote but who don’t because the proper precautions haven’t been put into place. “Imagine the same kind of Wisconsin situation, but in an environment where people are really mobilized and energized and interested,” he said.

The Illinois bill mandates that voters be notified if their mailed-in ballot has been rejected, and up to two weeks to rectify this and cast their vote. While this is a good way to shore up voting rights, an ambiguous result after November 3rd could provoke nationwide anxiety. The country might have to accept an election that isn’t called until weeks later. The consequences of which could be a serious discrepancy in the policy decisions that would result from a delayed transfer of power in transition.

Dietrich says the Illinois bill was written to be as clear as possible so that local election authorities could easily follow them so that procedures would run smoothly.

“It is fairly easy to understand because it pertains to voting, which is something that we all do,” Dietrich said. “It was written for an audience that they knew people would need this information.”

By contrast, Young sees the coming months as an uphill battle to making sure everyone can access their right to vote, with the amount of change that could be instigated from November making the situation critical.

“It's really hard to have a consistent statewide message across a bunch of different communities about something as complicated as this,” Young said. “It matters how well we can get those people to the polls, there's so much that is of consequence. If you don't participate, you don't get all you could and all you can do is hope that the system produces for you."